Rendering flames out of the train's engine

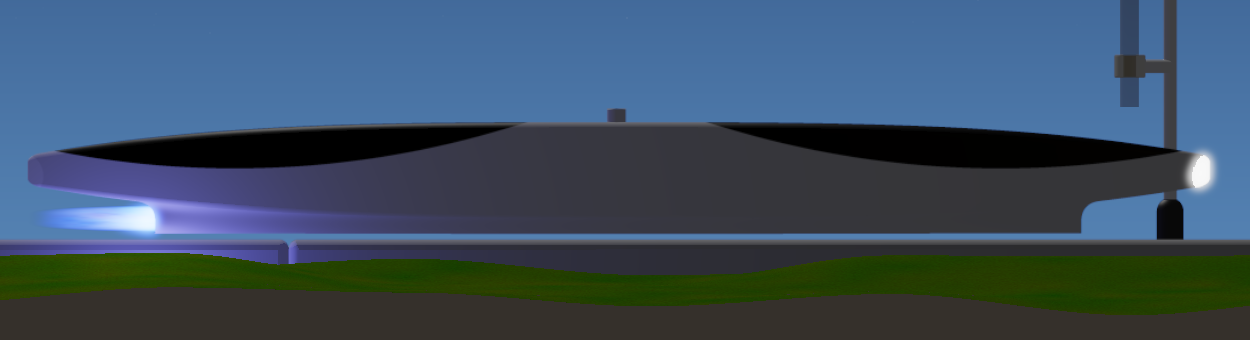

This is a little post I put together when working on visual effects for the demo for the “train in a tunnel” paradox. At the center of the demo is a train that can accelerate to speeds close to the speed of light. One of the improvements I wanted to make was to add a flame or something to highlight the moments when the train is accelerating.

The question for me was how to implement this flame. While I am not aiming for this visual effect to be 100% accurate, I still want to make sure it is roughly consistent with relativistic physics. When thinking about this problem, I was a bit confused at first. The flame itself is made by gas which moves: how does this affect the appearance of the flame when seen from different reference frames?

It was clear that the first thing to do was creating a rough physical model of the flame and then study how it appears to different observers.

A simple model for a flame

Let’s assume the train is capable of travelling at a maximum speed \(c \betat\) with respect to the ground and is propelled by a “flame” of particles travelling at speed \(\betap > \betat\) with respect to the engine. Note that in this article we denote with \(c\) the speed of light and we use the letter \(\beta\) for speeds normalized with respect to \(c\), so that \(c\beta\) is the actual speed.

Let’s say the train has a point-like engine that emits particles every \(\taue\) seconds, where \(\taue\) is the proper time with respect to the engine and the train. Let’s also assume that the particles are alive for \(\taup\) seconds, where \(\taup\) is the lifetime measured from the particles’ own reference frame. Let’s now try to determine the length of the the trail/flame left by the train’s engine.

Situation 1: the train is at rest and has just turned the engine on

An observer on the ground (or on the train) will see particles being emitted every \(\taue\) seconds and travelling with speed \(\betap\). Therefore the particles will cover a distance \(L = c \betap \gammap \taup\), where the factor \(\gammap\) accounts for the time dilation affecting the moving particles. It should be noted that \(L\) grows monotonically with the speed \(\betap\). The particles are also seen travelling a distance \(d = c \betap \taue\) from each other.

This is also what passengers on the train will always report: the flame having a length \(c \betap \gammap \taup\) and the particles in the flame having a spacing \(c \betap \taue\).

Situation 2: the train is at full speed

An observer on the ground will now see the train travelling in one direction and the particles in the flame travelling in the opposite direction. If the train is travelling with velocity \(\betap\) towards the right, then the particles will be travelling towards the left with a reduced speed with respect to the previously considered scenario. It follows that the flame should be seen as length-contracted by the following amount:

\[\frac{L'}{L} = \frac{c \betap' \gammap' \taup + c \betat \gammap' \taup}{c \betap \gammap \taup} = \frac{(\betap' + \betat) \gammap'}{\betap \gammap}\]\(\betap'\) is the velocity of the particles seen from the ground when the train is moving at full speed and \(\gammap'\) is the corresponding gamma factor. Note that the length of the flame seen from the ground receives contributions from both the particles’ movement and the train’s movement: after all the length is measured from the engine.

\(\betap'\) can be computed using the relativistic law of composition of velocities:

\[\betap' = \frac{\betap - \betat}{1 - \betap \betat},\]which gives:

\[\gammap' = \frac{1 - \betap \betat}{\sqrt{(1 - \betap \betat)^2 - (\betap - \betat)^2}} = \gammap \gammat (1 - \betap \betat),\]and yields:

\[\frac{L'}{L} = \frac{(\betap' + \betat) \gammap \gammat (1 - \betap \betat)}{\betap \gammap} = \frac{1}{\gammat},\]which tells us that the flame Lorentz-contracts as if it were a part of the train’s body.

This shouldn’t be too suprising. Observers on the train could put two marks where they see the particle emerge and vanish, i.e. at the front and on the tail of the flame. Every observer should agree that the flames emerge from one mark and vanish on the other. As the marks Lortentz-contract for an observer that sees the train moving, we conclude that also the flame must do the same. This reasoning makes all the calculations unnecessary and still I find it interesting to go through them and see that they are consistent with the simpler reasoning.

Concerning the spacing between particles, we can calculate it as \(c (\betap' + \betat) \taue'\), where \(\betap'\) and \(\betat\) are the velocity of the particles and the train as seen from the ground, while \(\taue'\) is the time between the emissions of two consecutive particles. \(\taue'\) is time dilated: \(\taue' = \gammat \taue\) and therefore we get:

\[d' = c (\betap' + \betat) \taue' = c \frac{\betap (1 - \betat^2)}{1 - \betap \betat} \gammat \taue = \frac{c \betap \taue}{\gammat(1 - \betap \betat)},\]and,

\[\frac{d'}{d} = \frac{1}{\gammat(1 - \betap \betat)}.\]If the particles travel with the same speed as the train, we simply get \(d'/d = \gammat\), which is what we expect. In this case, indeed we have \(d = c\betat\taue\) and \(d' = c\betat\taue' = c\betat\gammat\taue\). We assume \(\betap > \betat\), therefore:

\[\gammat \le \frac{d'}{d} \le \frac{\gammap^2}{\gammat}.\]In general, the spacing between particles is greater when seen from the ground, when the flame is also shorter.