Collision avoidance

Introduction

This article is a follow up to the article I wrote about the “Latency” of relativistic dynamics, where I was discussing problems emerging when implementing collision dynamics for relativistic rigid bodies. In this article I will be exploring a different approach: rather than having the body react to collisions, I want to design an algorithm that prevents collisions in the first place.

Let’s try to formalize a bit better what we are trying to do. We have a point-like object, a particle say. This particle can be moved by the player, who can – via a game controller or a keyboard – determine the current acceleration of the particle. The particle, however, must remain confined inside a given region of space. We want this confinement to happen thanks to an algorithm that corrects the acceleration provided by the player. There is one final element to clarify. At all times the total acceleration experienced by the particle must have magnitude below a given limit, the maximum acceleration, \(\newcommand{\smin}{s_{\min}} \newcommand{\amax}{a_{\max}} \newcommand{\vmax}{v_{\max}} \newcommand{\vr}{\mathbf{r}} \newcommand{\vv}{\mathbf{v}} \newcommand{\va}{\mathbf{a}} \newcommand{\vap}{\mathbf{a}_{\mathrm{p}}} \newcommand{\uv}{\hat{\mathbf{v}}} \amax\). These are the main “rules of the game”.

The issue is then that the player can gradually accelerate the particle to a velocity that is so big that a collision with the walls is unavoidable. The collision avoidance algorithm (simply called “algorithm” from now on) must detect when this critical condition is about to occur and ensure collisions can always be avoided in the future by applying an acceleration not stronger than \(\amax\). Importantly, the algorithm should be as little intrusive as possible. It should correct the acceleration set by the player only when it is absolutely necessary to avoid collisions. It is important that the player feels in control!

Classical version

We assume the container is described by an SDF function, \(s(\vr)\). This function is positive inside the container, negative outside the container and zero at its boundaries. The absolute value of the function tells us how far we are from the nearest wall.

We can start by making an observation: the distance that a particle requires to change its velocity from \(v\) to zero with an acceleration \(\amax\) applied in the direction opposite to the velocity is \(\smin(v) = v^2 / 2\amax\). We can call \(\smin(v)\) “braking distance” for the velocity \(v\) and acceleration \(\amax\). As long as the current distance from the nearest wall is greater than the braking distance, i.e. \(s(\vr) \ge \smin\), we are able to prevent the particle from crashing through any walls. The same condition can be expressed in terms of a maximum velocity: collisions can be prevented for sure if the velocity of the particle keeps below a maximum velocity, \(\vmax(\vr) = \sqrt{2\amax s(\vr)}\).

One strategy could then be for the algorithm to do nothing when \(v < \vmax(\vr)\). In this case, the player is able to control the particle without any interference. When \(v \ge \vmax(\vr)\), however, the algorithm kicks in. It decelerates the particle with acceleration \(\amax\) in the direction opposite to the current velocity, completely disregardomg input from the player. This strategy has some issues. The main one is that the player completely looses control of the particle when the algorithm kicks in. This could happen even if the particle is far from any walls. Clearly, we need the algorithm to kick in before the critical condition is reached.

Let’s then introduce a safety factor, \(\sigma\), a non-negative number smaller than 1. The new strategy will be the following. The algorithm kicks in only when \(v \ge \sigma \vmax(\vr)\), or equivalently:

\[\frac{v}{\vmax(\vr)} \ge \sigma.\]When this happens, the algorithm applies a correction to the acceleration as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \va = (1 - \lambda) \, \vap - \lambda \, \amax\,\uv, \label{eq:acc_blending} \end{equation}\]where \(\vap\) is the input acceleration from the player, \(\uv = \vv / v\) is a unit vector oriented along the current velocity, \(\lambda\) is a factor – to be determined – that “blends” the two accelerations together. We call this factor “criticality”.

How do we choose \(\lambda\)? Well, it makes sense for it to gradually go from 0 to 1 as \(\frac{v}{\vmax(\vr)}\) increases from \(\sigma\) to 1. For example,

\[\lambda = \frac{\frac{v}{\vmax} - \sigma}{1 - \sigma}.\]Other formulas are possible. For example,

\[\lambda = \frac{\frac{v^2}{\vmax^2} - \sigma^2}{1 - \sigma^2}.\]There is a final detail to take care of: Eq. \eqref{eq:acc_blending} can result in an acceleration that is greater than \(\amax\). Take, for example, the case where \(\vap\) is oriented along \(-\vv\). This issue can be handled by introducing a final step where the acceleration is rescaled when its norm exceeds \(\amax\).

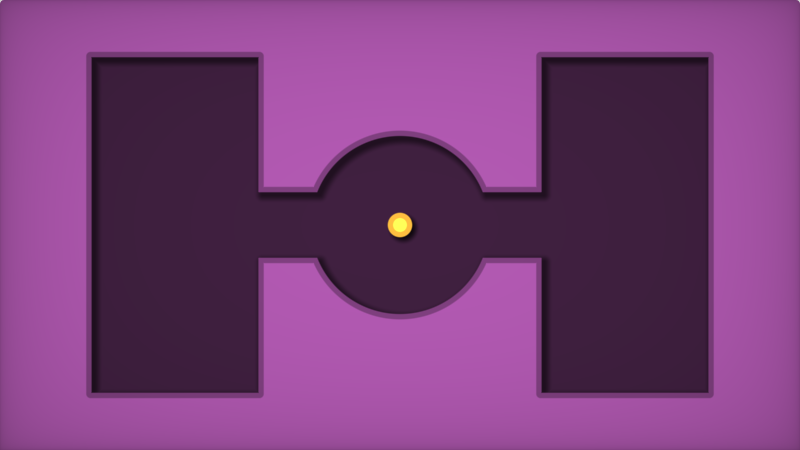

I provide a simple implementation of this algorithm in Shadertoy.

The implementation limits itself to classical physics as done above. You can steer the yellow ball using the arrows in the keyboard and stop the ball completely by pressing the space bar. I am sorry, but this demo requires a keyboard and therefore does not work well on mobile. Well, I guess this is a common problem for interactive Shadertoy demos.